Over the millennia, toothache has caused untold sleepless nights and hours of suffering. Some descriptions from the literature include “among the worst of tortures,” “one of the sharpest of Pains,” “[a] gnawing vengeance,” “an inferno of pain,” and “A vile toothache comes to remind me I am mortal.” Afflicted individuals in the past appealed to supernatural forces with charms and incantations, while healers and practitioners applied plasters, purgatives, botanicals and cautery to try to cure toothache. Extraction was considered a dangerous last resort to be used only if the painful tooth was loose. Various concoctions were formulated to irritate the gums and loosen the offending tooth.

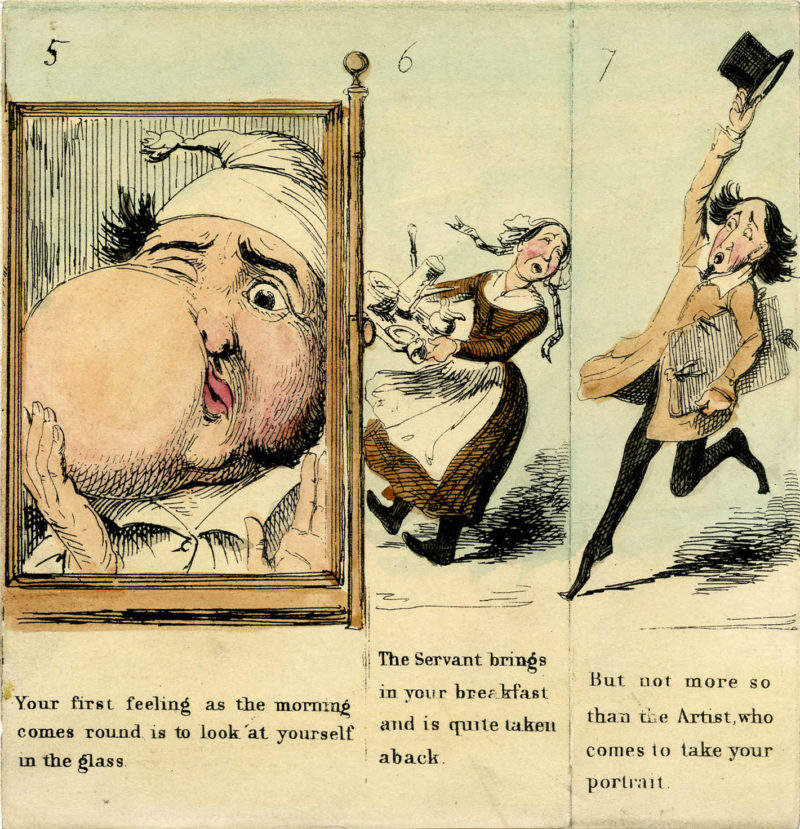

Cascading negative effects of a toothache, as imagined by Mayhew and illustrated by Cruikshank in their 1849 booklet entitled “The Tooth-ache.” © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license

In medieval times, metal tooth extractors were unrefined, generic forceps lacking in tooth size adjustability. With this type of instrument, the force necessary to draw an immobile tooth could cause it to break, leaving behind embedded roots, or damage the surrounding teeth, tissue or bone. Apparently, 10% of fatalities during the Middle Ages can be attributed to infections from mishandled dental operations or unsanitary procedures. But ultimately, although a dreaded choice, extraction was necessary if an agonizing toothache persisted.

Among the early European instruments designed specifically for tooth extraction were the pelican and the toothkey. They were similar in that a metal “claw” was placed over the crown of the tooth and a fulcrum (“bolster”) against the gum. Both relied on pressure applied to a handle but the force and motion required to lever the tooth out of its socket differed. The pelican instrument, so named for its claw’s similarity to the bird’s beak, was used for nearly 500 years! From the 14th to 19th centuries, it was modified by variations in shape, size and adjustability of the handle, bolster, shaft and claw. During a procedure, the hooked claw was placed over the crown and the handle pivoted in the same plane until the tooth was secured between the claw’s hook on the lingual (tongue) side and the bolster on the buccal (cheek-side) gum. Downward pressure on the handle elevated the tooth laterally. Fauchard described using the pelican to loosen the tooth by “shaking” it. Although in unskilled hands the pelican could cause significant damage, perhaps, in comparison to the toothkey, it encouraged a gentler, more restrained technique, which may explain its longevity.

The original toothkey (or “key”), circa 1740, consisted of a straight metal shaft with a large ring-like handle at one end and a hinged “claw” at the other. It resembled a door key of the time, and, after engaging the tooth crown with the claw, the extraction motion was similar to turning a key in a lock.

Early American extraction instrument

Courtesy of Abrams Publishing, New York, NY — Ring, 1985

From England its use spread to the Continent by the mid 1700s, and to America in the later half of the century, where the first US dental patent was issued for a “tooth extractor” in 1797. For 100 years, from 1750 to 1850, the key was the preferred instrument of extraction, apparently because the procedure was quick. Embellishments and improvements along the way resulted in variously angled shafts, different handle shapes made of wood, ivory, horn or mother of pearl, changes in bolster (fulcrum) size, shape and covering, and advances in claw grasp, mobility and interchangeability.

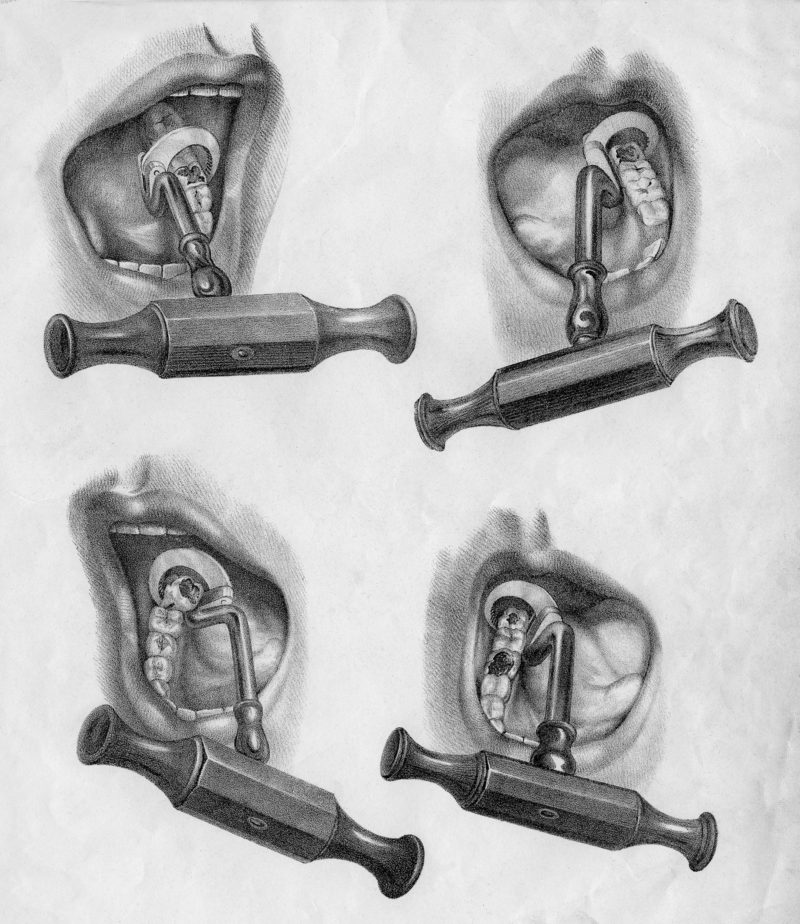

Toothkey in Use — Goddard, 1844

University of the Pacific Permanent Collection, Donor: Unknown

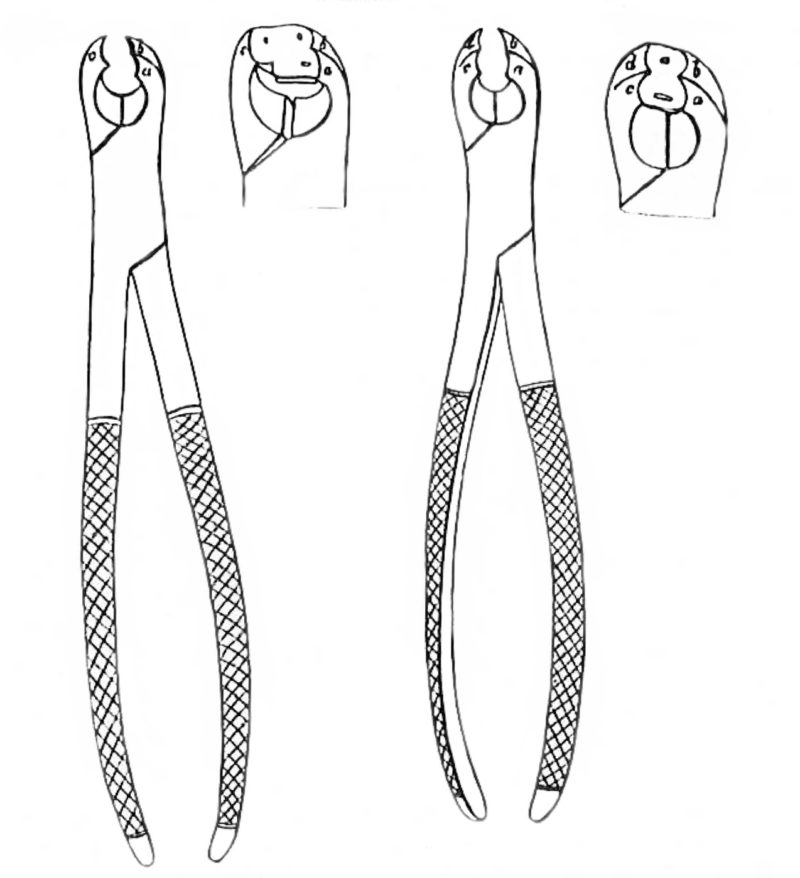

Forceps may be the oldest dental instrument, used throughout the ages by toothdrawers to loosen and extract teeth. But not until the 1840s, when Sir John Tomes created efficient extraction forceps, designed to grasp different tooth shapes more precisely, did these instruments become preferable. Eventually the “dangerous and barbarous” toothkey became obsolete and, by 1900, was expunged from the dental armamentarium.

— D.D.

Tomes’ Forceps

Courtesy of Martino Publishing, Eastford, CT — Colyer, 2006

References

Anderson, T 2004, Dental treatment in Medieval England. BDJ 197:419-425; Atkinson, HF 2002, Some early dental extraction instruments including the pelican, bird or axe? Aust Dent J 47(2):90-93; Bennion, E 1986, Antique Dental Instruments, London: Sotheby’s Publ, Phillip Wilson Publ; Busch, W 2003, Tooth keys. J Hist Dent 51(2):57-59; Colyer, F 2006, Old Instruments Used For Extracting Teeth, Mansfield Centre, CT: Martino Publ; Fauchard, P 1728, Le Chirurgian Dentist, ou Traité des Dents, Paris: Jean Mariette; Foley, GPH 1972, Foley’s Footnotes: A Treasury of Dentistry, Wallingford, PA: Washington Square East Publ; Hyson, Jr, JM 2005, The dental key: a dangerous and barbarous instrument. J Hist Dent 53(3):95-96; Ring, ME 1985, Dentistry: An Illustrated History, New York: Abrams/Mosby Publ.

Caption References

Bennion, E 1986 Antique Dental Instruments, London: Sotheby’s Publ, Phillip Wilson Publ; Colyer, F 2006 Old Instruments Used For Extracting Teeth, Mansfield Centre, CT: Martino Publ; “Hints and Queries: An ancient extracting instrument.” 1891 Dental Cosmos 33(6):501, June; Ring, ME 1985 Dentistry: An Illustrated History, New York: Abrams/Mosby Publ; Swank, S, pers comm, March 3, 2016.

Photographs by Jon Draper