Before the mid-19th century dental cavities were prepared very slowly. Long, slender burs were often simply twirled between finger and thumb to remove decay. Or they could be spun around with a vigorous back and forth sawing motion on a small bow. The tedious nuisance of excavation provoked shortcuts. Holes were sometimes filled with just a shrug and a plug of lead or gutta percha, skipping the caries removal altogether.

The promise of speed focused both professional and public attention on the drill. James Morrison took out patents for a dental engine powered by a foot treadle in 1872. (An electric engine had been introduced in 1868, but it failed commercially, since few offices had electricity.) Morrison’s system of pulleys was adapted for drills right up to the end of World War II.

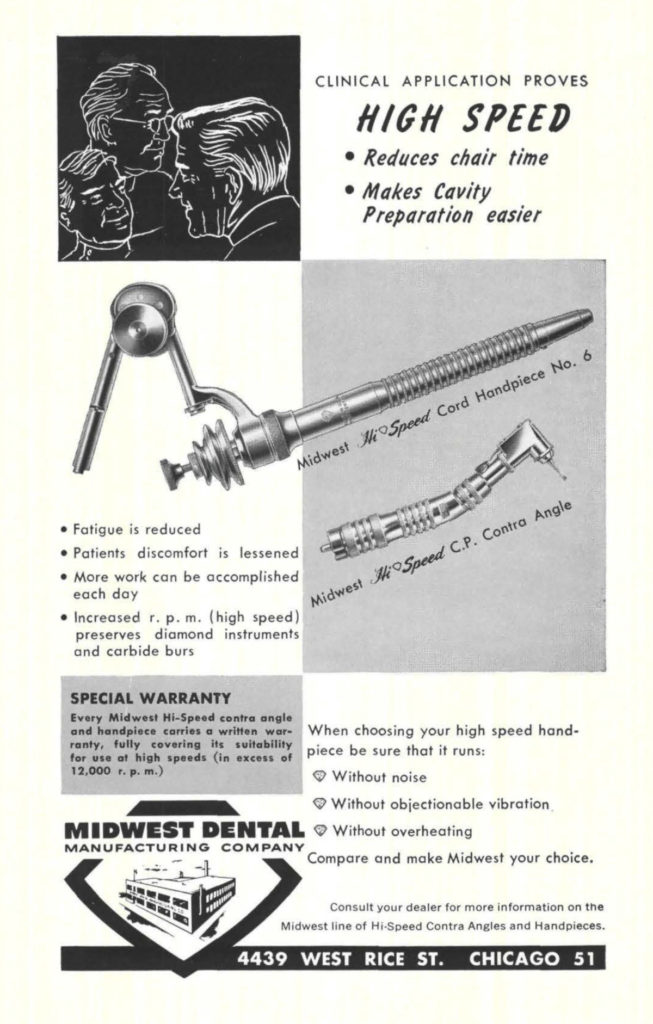

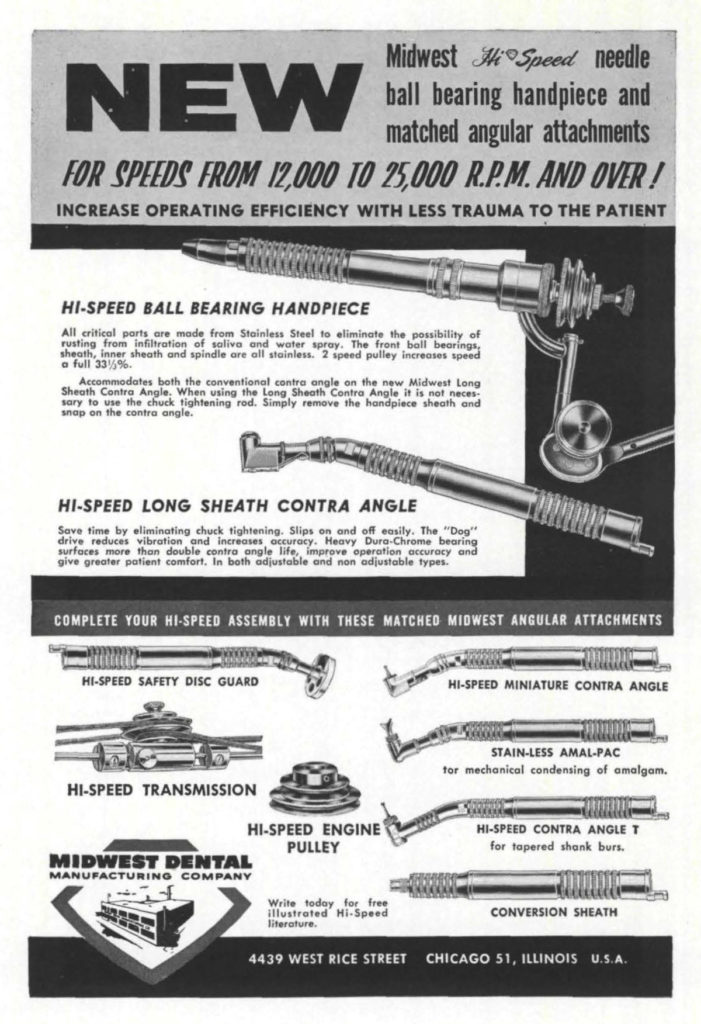

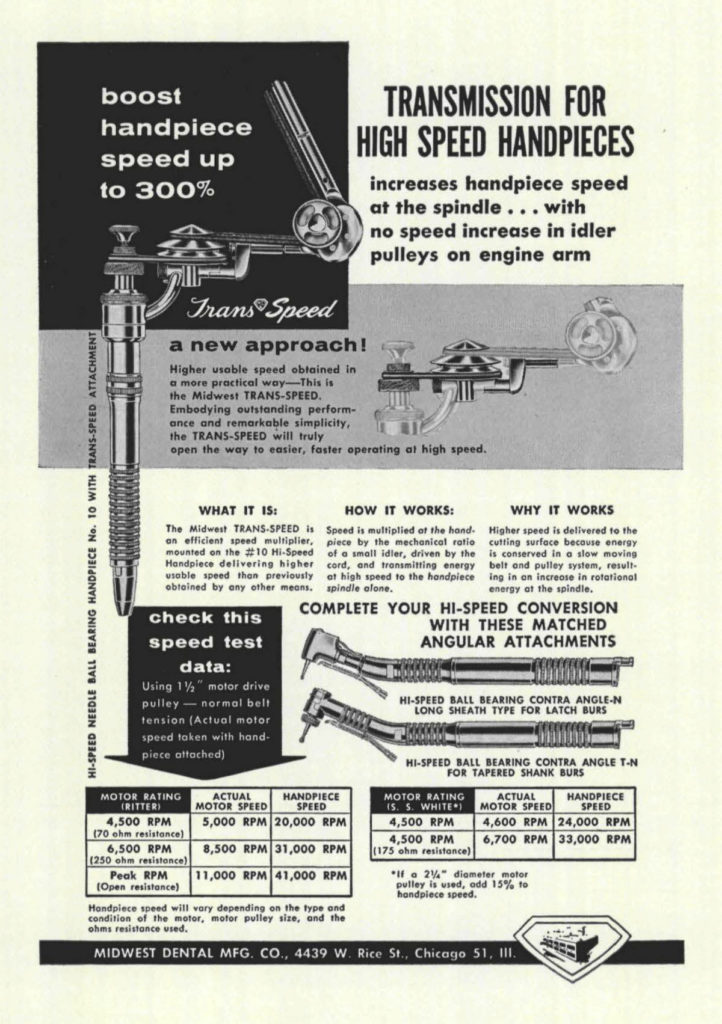

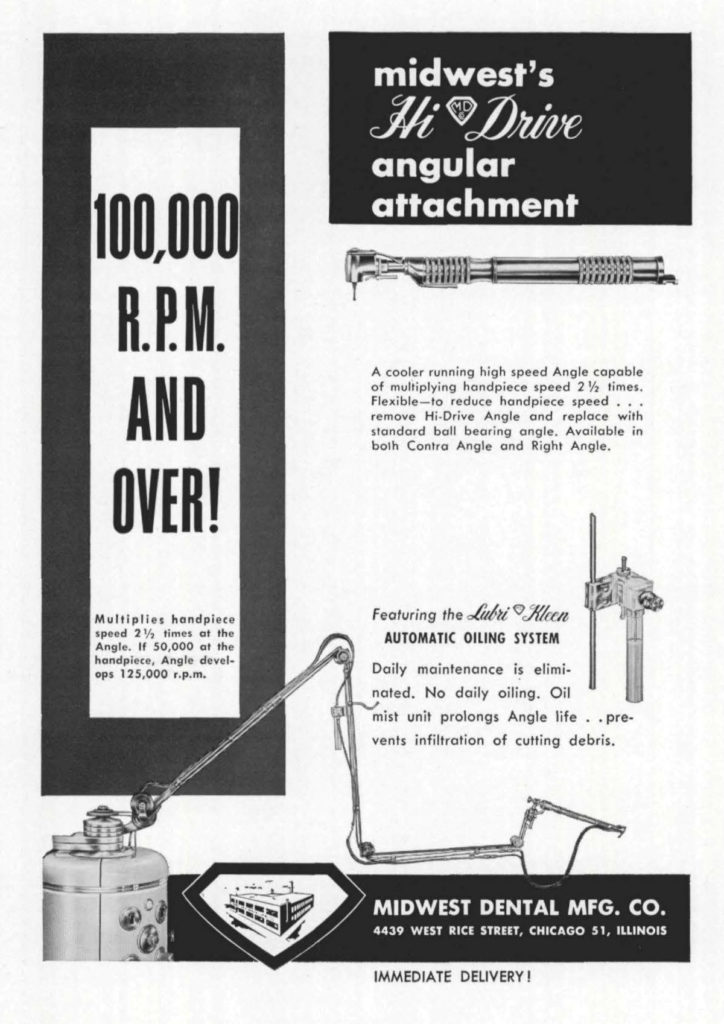

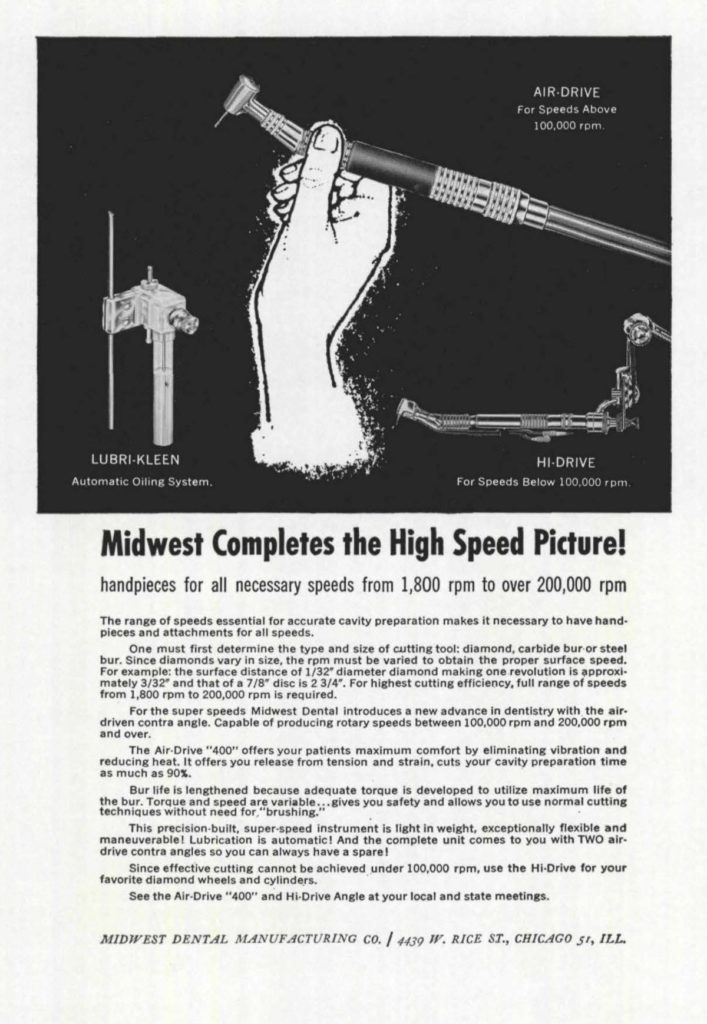

The dental engine made the drill the workhorse of dentistry. Operative procedures instead of extractions became bread and butter dentistry. Nevertheless, even with the improved technology, the handpiece was known for its memorable vibrations. The problem was that the average belt-driven, gear angle handpiece in 1938 rumbled along at a speed of only 2000 rpm. After the war, better cutting diamond and tungsten-carbine burs came into wider use, which in turn encouraged higher motor speeds. By 1950, 6500 rpm was the standard for dental handpieces. Then airplane designers noticed the windmill. The turbines that boosted jets up to mach speeds did the same for dental drills. A burst of handpiece design ideas and patents, improving mechanics and increasing speed, emerged during the decade of the 1950s. In 1957, Washington DC dentist John Borden filed a patent for a practical air turbine handpiece, called the Airotor, which, with bur speeds of 250,000, utterly changed the pace of the profession.

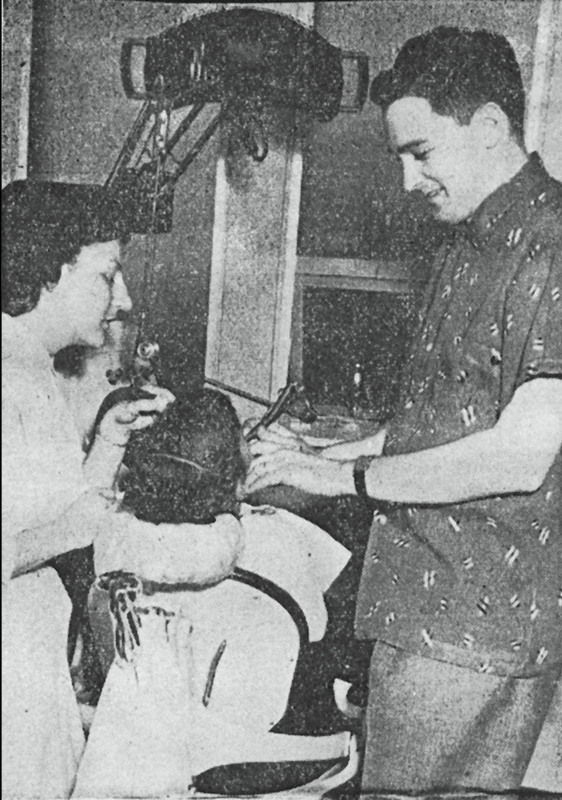

Among the first to share the faith was P&S assistant clinical professor of operative dentistry Arthur A Dugoni. He had advocated use of the new belt-driven high speed handpieces in the mid 50s and arranged with the manufacturers to equip the senior clinic with air turbine demonstration units. “The impact upon the dental profession, and the public acceptance of and demand for increased speeds has aided in motivating our teaching program,” Dugoni explained to Contact Point that same year. “However, the prime reason for including increased speeds in undergraduate teaching is the advantage of producing the highest quality dentistry with increased comfort to the patient.”

— D.D.

References

Curtis, EK 1995 A Century of Smiles. University of the Pacific School of Dentistry; Dugoni, AA 1959 Philosophy of high-speed teaching for undergraduates. Contact Point 38(2):34-35, 39-40; Flatland, L 1988 Descriptions for Evolution in Hand, UOP School of Dentistry, Ward Museum exhibit; Kurtzman, GM 2005 Handpieces: the drill on high speeds. CERP 9(10):2-5; “Local Dentist Demonstrates New High Speed Drill Equipment” SF Examiner April, 1957; Sockwell, CL 1963 Belt driven super speed equipment. J N Carolina Dent Soc 46:114-21; Sockwell, CL 1971 Dental handpieces and rotary cutting instruments. Dent Clin North Am 15:219-44; “SSF Dentist Displays Drill” SF Examiner 2 Dec 1956, Sec 1, p 21; Stephens RR 1987 Dental handpiece history. Aust Dent J 32(1):58-62; Vinski I 1979 Two hundred and fifty years of rotary instruments in dentistry. Br Dent J 146:217-23

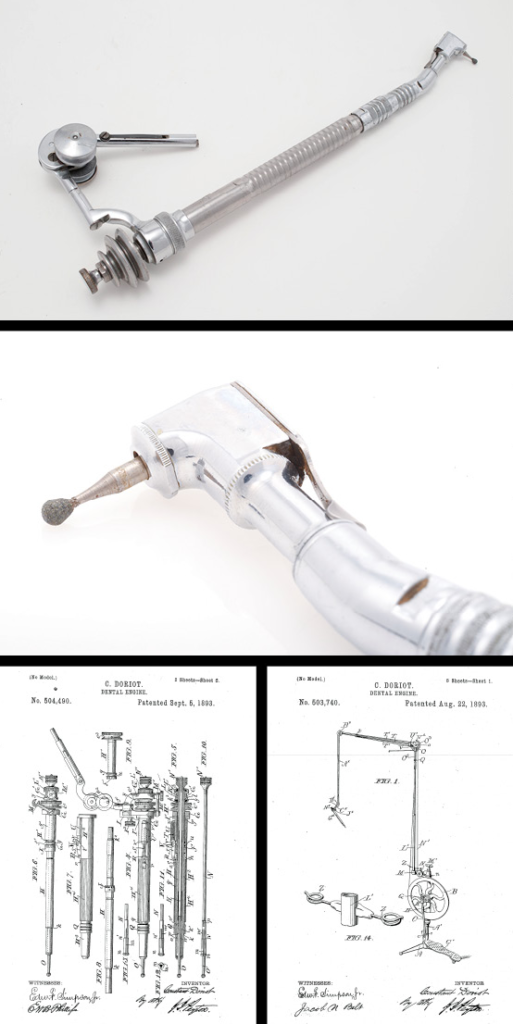

Slide Patent References

Doriot, Constant (1893) Dental Engine. US Patent 504,490. Filed March 11, 1893, and issued September 5, 1893; Doriot, Constant (1893) Dental Engine. US Patent 503,740. Filed March 2, 1893, and issued August 22, 1893; Borden, John V (1962) Dental Handpiece Construction. US Patent 3,061,930. Filed July 28, 1959, and issued November 6, 1962; Borden, John V (1962) Stabilized Turbine for Dental Handpiece. US patent 3,055,112. Filed July 28, 1959, and issued September 25, 1962

Photographs by Jon Draper

Exhibit Slides

Click on slides to see larger versions.