In the past, dentists did much of their own lab work. Consequently, they spent a good deal of time annealing, softening, vaporizing, melting, soldering, baking, and curing a variety of substances in their laboratories. This exhibit explores some of the 19th to mid-20th century heating devices, accessories, and methods used by dentists to accomplish the many tasks of the profession, among which included filling teeth, making crowns, and fabricating dentures.

Crinkled Gold

The use of gold leaf and foil as dental filling materials was first noted in the 15th century. Requiring considerable dexterity, only the best dentists performed tooth fillings during the 18th century, with gold leaf following lead leaf in popularity. By the 19th century, annealing small sponge pellets (made from crinkled gold foil) over a “spirit” (alcohol) flame was discovered to improve the gold’s cohesiveness and shaping properties. Initially, the dentist acquired gold filling material by taking gold coins to a gold-beater for flattening and thinning. Later, dentists preferred to purchase manufactured pure gold foil, as it proved to make a superior filling.

Specially designed gold foil “plugging” instruments were used in the mid-1800s, along with mallets, to facilitate the use of hand pressure for compacting gold filings. Later in the century, these instruments were succeeded by automatic condensers — spring-loaded devices that pounded the gold foil into the tooth cavity. The dentist’s goal was to achieve complete compression and adhesion of compacted gold in the prepared cavity. An alcohol lamp or annealing tray, close at hand, provided the heat necessary to practice the gold foil technique successfully.

Fabricated Dentures

Prior to the mid-1800s, denture fabrication was an intricate and expensive process of attaching pins to porcelain teeth and soldering them to a suitable cast denture base, with costly gold being the best base material. Natural rubber, hardened by the vulcanization (heating) process, made denture construction easier and more affordable, and became the favored base material for the succeeding 100 years. By the mid-1900s, polymer acrylics superseded vulcanized rubber as the preferred denture base substance. An important aesthetic stage of denture fabrication, called “waxing up,” involved using softened wax for precise placement of artificial teeth along the model of a patient’s toothless ridge, and for creating wax gingiva (gums) with realistic contours between and surrounding the artificial teeth. Flames from an alcohol torch were used to soften the wax along the ridge, and the tip of a spatula, when heated over a Bunsen burner or warmer, was effective in making life-like gum features in the wax.

Lost Wax

Thus far, the lost-wax (aka investment) casting method has been traced back 6,000 years to an amulet from the Indus Valley civilization. As Asgar describes the process of casting metals by the lost-wax technique — “All that is known is that somewhere along the line — it may have been in ancient Egypt or in ancient China — someone conceived of the idea of making a wax replica of an item to be cast, surrounding this replica with an investment material, letting the investment harden, then melting and burning out the wax, thus producing a mold having a highly intricate and accurate cavity. The next steps were melting the metal and pouring it into the cavity.”

In the late 1700s to early 1800s, when dentists realized the value of producing artificial porcelain teeth for prosthetic purposes, they began to practice the lost-wax method using furnaces or muffles as the heat source. Eventually, all 19th century dentists’ laboratories included a burn-out oven, wax, special wax spatulas, plaster of Paris, a casting machine and other items to expedite the casting of denture bases, inlays, and crowns using the lost-wax technique.

Thrown Gold

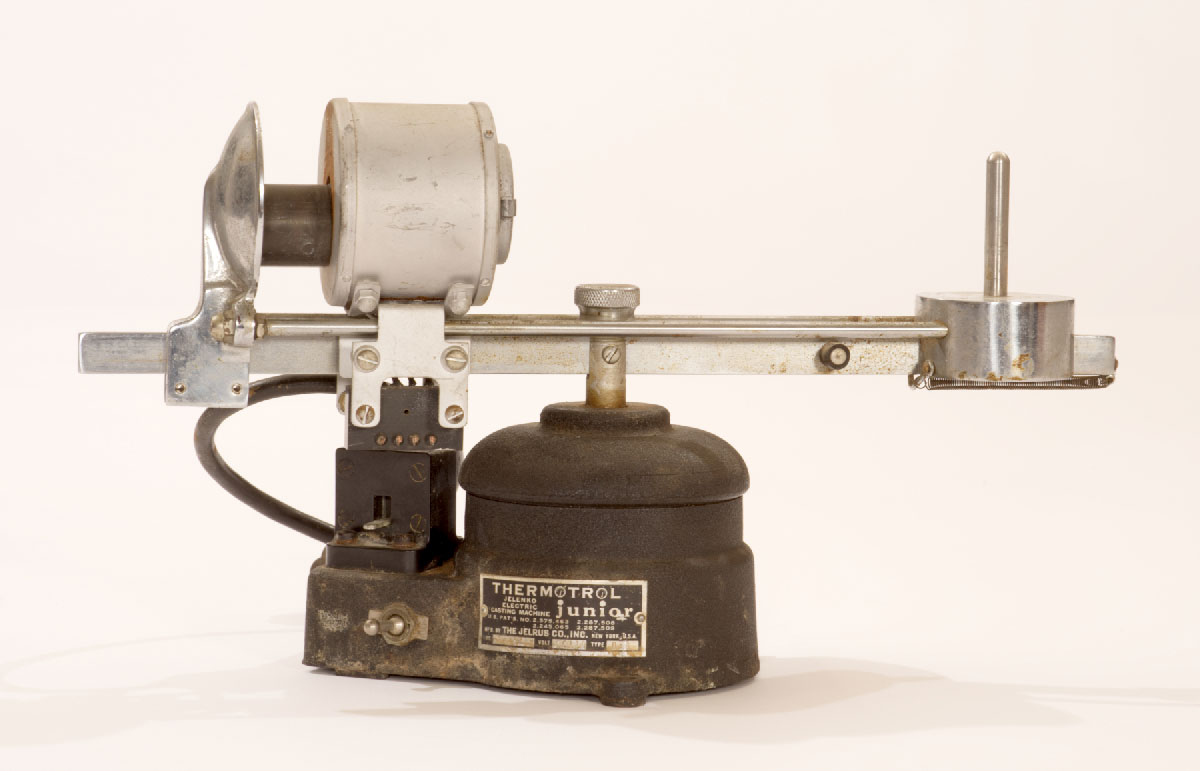

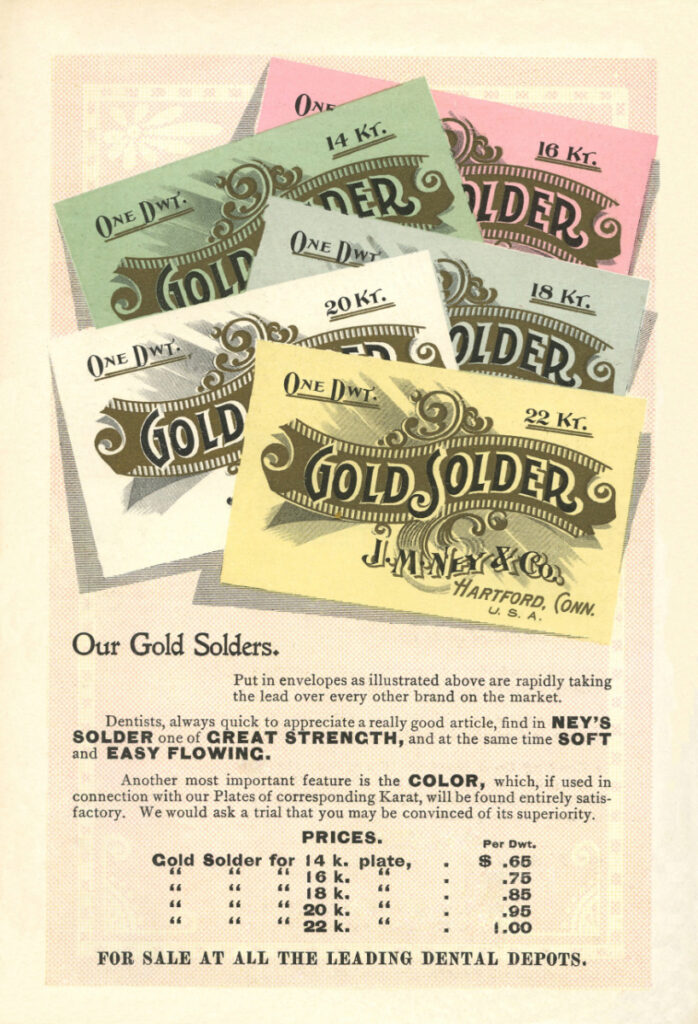

Plaster of Paris (or “stone”) for making investments was introduced to American dentistry in 1820, and the process of casting denture plates from molten gold (or gold solder) was improved. The successful casting of gold denture bases, however, was not routine until the invention of the casting machine in the early 1900s. Similarly, making quality inlay and crown casts became easier and faster using this device. Typically, the early 20th century dentist’s laboratory included gold plate to be melted, blowpipes for reaching adequate gold-melting temperatures, and a casting machine that used centrifugal force to “throw” the molten gold from the crucible into the adjacent investment.

Cured Rubber

During the early 1800s, because adequate sedation was unavailable, most people chose to retain their “rotten” teeth rather than subject themselves to the pain of having them extracted. In 1844, when Horrace Wells discovered anesthesia, dentists were suddenly asked by patients to extract all their “troublesome, aching and infected teeth.” This left millions of edentulous people who could not afford the expensive gold-based dentures available at the time.

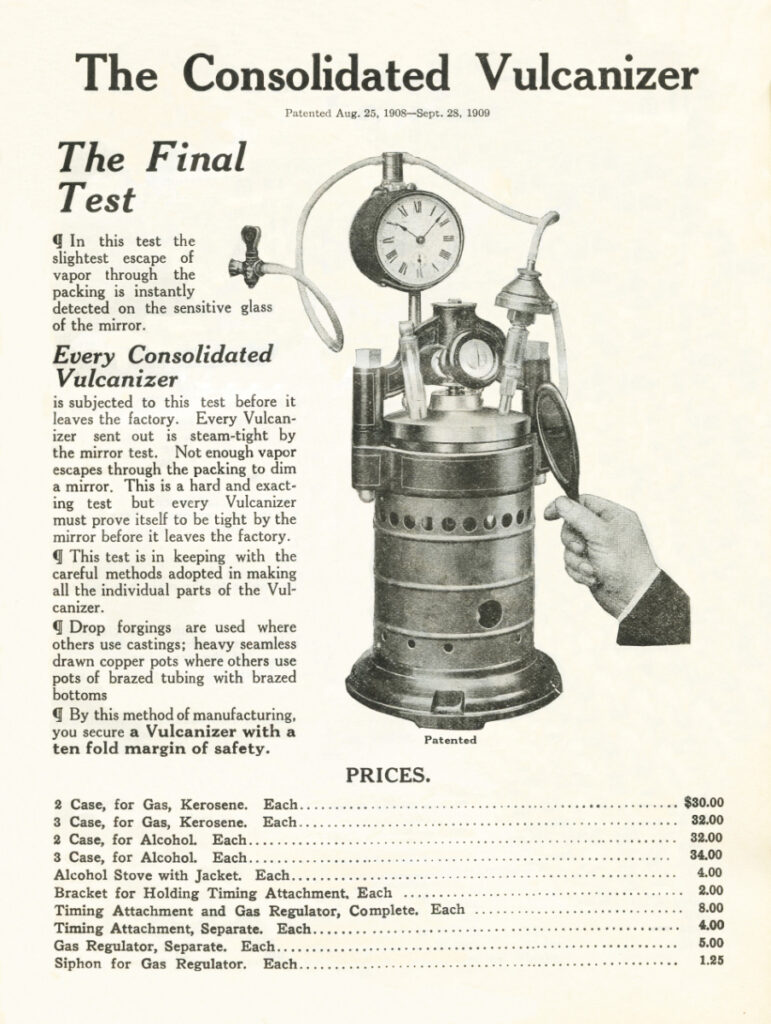

With the mid-1800’s discovery that natural viscous rubber could 1) hold artificial teeth, 2) accurately reflect gum contours, and 3) be “cured” to a suitably hard consistency, known as vulcanization, denture fabrication was revolutionized. Vulcanite dentures were easier and cheaper for the dentist to make, and patients preferred them over the less comfortable carved ivory or bone and the more costly swaged gold options.

The patents for hardening soft natural rubber, and for improving denture fabrication using natural rubber, were held by the Goodyear Rubber Company and Dr. John A. Cummings, a Boston dentist. Unfortunately, from 1851 to 1881, these two patents forced the dentist making vulcanite dentures to acquire an expensive license to do so. The resulting controversy caused enraged dentists to form organized groups for challenging Goodyear in the courts. The dispute culminated in the 1879 murder of Josiah Bacon, the Goodyear Dental Vulcanite Company’s Treasurer and ruthless patent enforcer, by Dr. Samuel P. Chalfant, DDS, a San Francisco dentist. Apparently, Dr. Chalfant had become exasperated by Mr. Bacon relentlessly hounding him across the country for his unpaid license fees. Following that unfortunate incident, the Goodyear Company decided not to extend its patent rights, and, in 1881, the contentious era of vulcanite denture fabrication ended.

The steps for vulcanite denture preparation involved the usual waxing-up, placement in a metal dental flask, investment in “stone,” and vaporizing of the wax (lost-wax technique) in a burn-out oven. With the hollowed denture pattern still deep inside, the flask was opened, packed with vulcanite rubber, clamped shut, and placed in a vulcanite oven for “curing” under high pressure heating.

As described by Gabell, the denture vulcanization process, though faster and less expensive than other denture fabrication options, suffered from a variety of inconsistencies: “The difficulties arise from the series of physical changes which occur in the rubber during vulcanization. On heating, it becomes soft and viscous, flowing easily in wide channels, but with great difficulty over rough surfaces; it swells with great force, expanding 10 to 12 per cent from 60° to 320° F. But at 250° F. chemical changes cause a contraction of 4 per cent, which takes place more rapidly than the vulcanization and is practically complete before vulcanization is half done. As it cools rubber both shrinks and also becomes less and less fluid. The shrinkage is about 10 to 12 per cent and is irresistible, and part of it must occur after the rubber has lost its fluidity. This will produce local hollows or a general shrinkage and an internal stress which may reappear, either at once or a considerable time afterwards, as a warp. Also rubber increases in weight (and in volume) 0.2 to 3 percent in proportion to the surface area. The expansion and shrinkage are, in practice, very irregular, as it is practically a contest between the rubber and the plaster, complicated by the force used to pack and close the flask and the gain in weight.”

The dental profession must have heaved a collective sign of relief, when, with the development of plastics during the early 20th century, acrylic gradually displaced vulcanized rubber as a more “user friendly” denture base material. — D.D.

With valuable input from Ernie Giachetti, DDS ’67, Preventive and Restorative Dentistry Department faculty member

Photographs by Jon Draper

Explore the galleries on the following pages. Click on slides to see larger versions.